Early Life

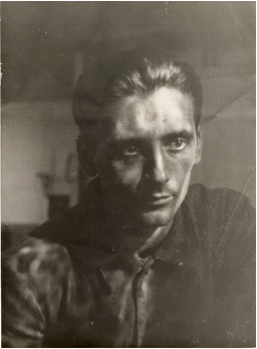

Hermann Gross was born in Lahr in Baden, Germany on

the 4th February 1904 and at the age of fourteen began his

art studies under Rudolf Yelin, a well known church

painter and stained-glassmaker in Stuttgart.

From 1919 to 1925 he attended the Württemberg Arts and

Crafts School, where he learned to become a gold- and

silversmith subsequently becoming the master pupil of

Professor Paul Haustein.

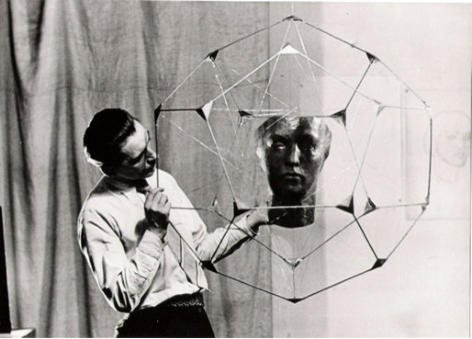

In 1925 he enrolled on a one-year course in engraving and

metal chasing at the State Academy of Fine and Applied

Arts in Berlin run by Professor Waldemar Raemisch. A year later he moved to Paris

where he worked with Robert Wlérick.

When Gross moved to Paris in 1928, he was accompanied by his partner, Hildegard

Friedrichs, author, and fashion illustrator. They shared a shed-like building in a

courtyard at 48 Avenue des Gobelins bordering Montparnasse.

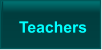

Gross had a circle of friends in Paris – mostly young

people at the beginning of their artistic careers. Among

them was Jean-Louis Barrault, who became one of

France’s most distinguished actors and directors –

perhaps best remembered for his portrayal of Hamlet

and as the mime in Marcel Carné’s film Les enfants du

paradis (1944).

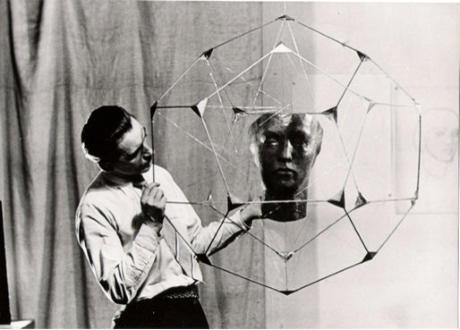

In 1929 Gross exhibited a metal sculpture entitled

Portrait de jeune fille repousse sur cuivre. at the Salon

d’Automne in Paris.

Suzy de Solidor

Suzy de Solidor was born in Deauville in 1900: her real name being Suzy Louise

Rocher. She changed her name to Suzy de Solidor when she moved to Paris in the

late 1920s. She was one of the first symbols of sexual emancipation in France during

the 1930s. Early in 1930, she became popular as a singer, opening a chic nightclub

called Boîte de Nuit which was one of the trendiest night spots in Paris. Suzy Solidor

did not hide her sexuality and sang songs that overtly revealed that she was gay. One

of the singer’s most famous publicity achievements was to become heralded as ‘the

most painted woman in the world’. She posed for some of the best-known artists of

the day including Jean Cocteau , Pablo Picasso , and Georges Braque. Her stipulation

for sitting was that she would be given the paintings to hang in her club. There are, in

total, around 150 paintings of Solidor. In Cagnes-sur-Mer, in the south of France,

there is a museum dedicated to her with a collection of 42 portraits all painted by

different artists. She died in 1983. It is not known whether she sat for Gross or

whether he based his work on occasional sightings of her at cabaret performances or

on the many paintings of her that would have been accessible in Paris at that time.

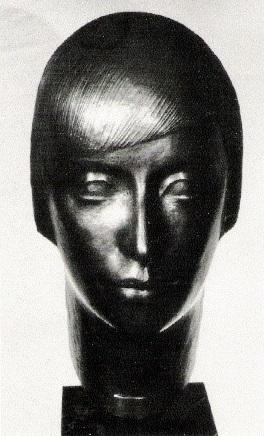

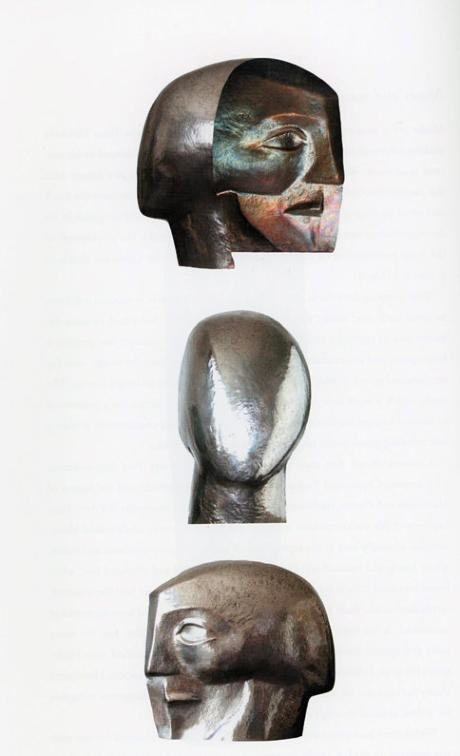

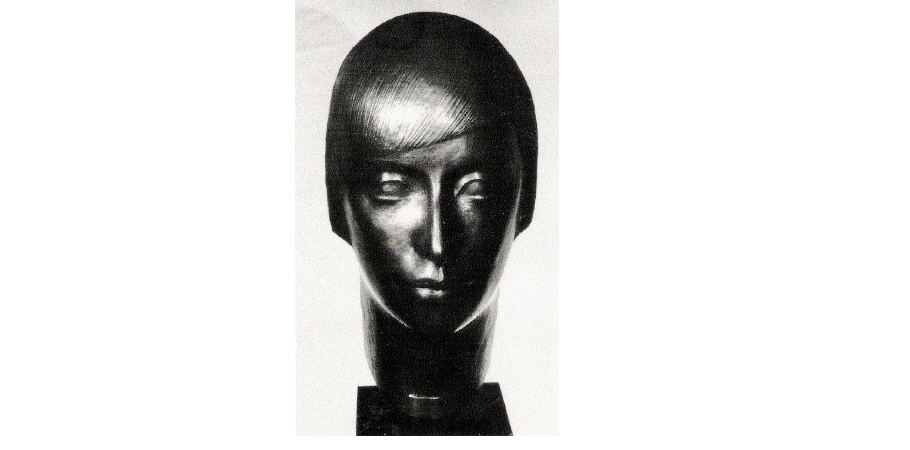

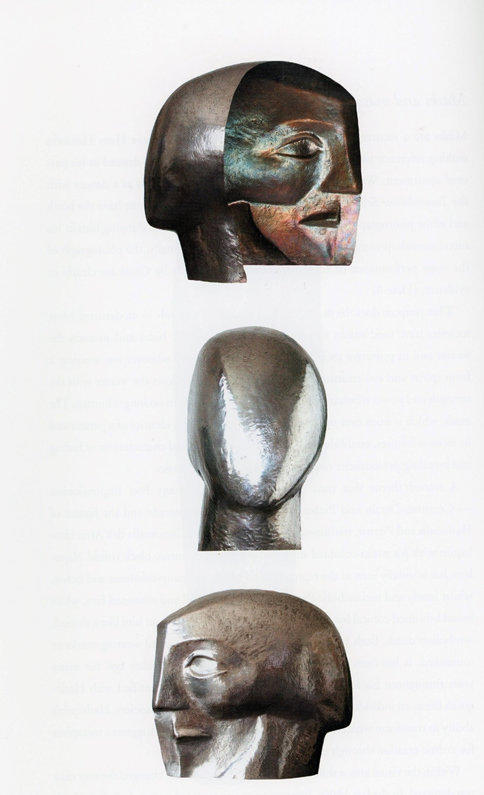

The Silver Head

The silver head created by Gross is of

particular interest. One quality that this

work possesses is playfulness – it is

challenging, teasing, and puzzling. This

playfulness offers both illusions and

allusions. One moment the head seems

to be one thing, the next moment it is

something else. An extraordinary

feature of the head is that from the

reverse side, the head takes on the

appearance of a Cubist painting. The

muted palette of bronze, pink, steel blue

and grey are strongly reminiscent of

certain portraits by Picasso. There can

be few examples of sculpture that

mysteriously dissolves into what

appears to be a painting.

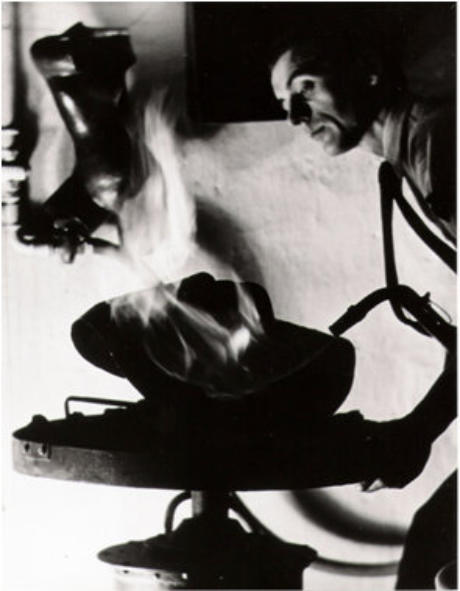

The colours are a natural result of the

process of oxidisation. We know that

some contemporary silversmiths

deliberately seek to achieve the oxidised

effect on their jewelry.

After her husband’s death Trude Sand

insisted that the head should be kept

highly polished and one must assume that this stricture applied solely to the exterior.

What are the aesthetic consequences? Whilst the polished surface quite literally

reflects the external world, the oxidised interior invites the viewer into it. The

untreated side provides an authentic face, whilst the polished side provides an

artificial face.

The head is teasing insofar as it presents the viewer with a series of further

paradoxes. Whilst the exterior of an object is usually that aspect that gains the

viewer’s attention, here it is the interior that appears to possess more character and

meaning. What is particularly intriguing is that Gross is inviting us to see behind the

mask, something that is rarely done. It is as if a taboo has been broken. To

emphasise this feeling of gaining new insights, we are presented with a face in which

the eye is dominant and rather like the Eye of Horus – the ancient Egyptian symbol

of indestructibility.

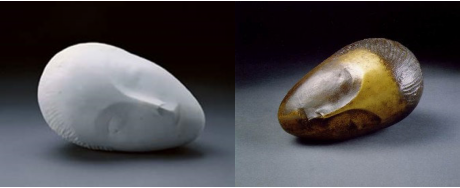

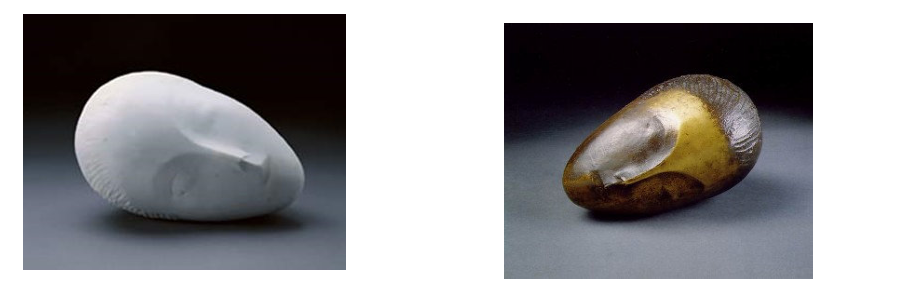

One of the most intriguing angles from which to view the head is from the back. Or

is it the back? Gross would have been aware of the work of Constantin Brancusi, for

he was working in Paris at the same time as Gross. He would have known of

Brancusi’s minimalist representations of the human face – The Sleeping Muse. The

strongly ovate shape of the face of The Sleeping Muse intentionally suggests an egg –

a symbol of birth or new life. In discussing the nature of his work Brancusi coined

the striking aphorism that “simplicity is complexity resolved”. So, when one moves

to a position to view the ‘rear’ of the head, the intrinsic complexity of the head

magically resolves into a simple Brancusian ovoid.

So, in this single artefact – the silver head – we have allusions not only to different

artistic genres but also to symbols of considerable power – indestructability, birth,

and rebirth. These, in turn, can be interpreted as signs of resurrection and hope –

themes that Gross pursued throughout his life. But then the question may be asked:

‘How can one be so confident that Gross was trying to communicate any of these

messages? The simple answer is that we do not know. But that question rather

misses the point. What Gross has succeeded in doing is stimulating the viewer to

reflect on its meaning. The Silver Head is now in the possession of Aberdeen Art

Gallery.

Gross left Paris in 1935 and returned to Germany.

Early Life

Hermann Gross was born in Lahr in

Baden, Germany on the 4th February

1904 and at the age of fourteen began his

art studies under Rudolf Yelin, a well

known church painter and stained-

glassmaker in Stuttgart.

From 1919 to 1925 he attended the

Württemberg Arts and Crafts School,

where he learned to become a gold- and

silversmith subsequently becoming the

master pupil of Professor Paul Haustein.

In 1925 he enrolled on a one-year course

in engraving and metal chasing at the

State Academy of Fine and Applied Arts

in Berlin run by Professor Waldemar

Raemisch. A year later he moved to Paris

where he worked with Robert Wlérick.

When Gross moved to Paris in 1928, he

was accompanied by his partner,

Hildegard Friedrichs, author, and

fashion illustrator. They shared a shed-

like building in a courtyard at 48 Avenue

des Gobelins bordering Montparnasse.

Gross had a circle of friends in Paris –

mostly young people at the beginning of

their artistic careers. Among them was

Jean-Louis Barrault, who became one of

France’s most distinguished actors and

directors – perhaps best remembered for

his portrayal of Hamlet and as the mime

in Marcel Carné’s film Les enfants du

paradis (1944).

In 1929 Gross exhibited a metal sculpture

entitled Portrait de jeune fille repousse

sur cuivre. at the Salon d’Automne in

Paris.

Suzy de Solidor

Suzy de Solidor was born in Deauville in

1900: her real name being Suzy Louise

Rocher. She changed her name to Suzy

de Solidor when she moved to Paris in

the late 1920s. She was one of the first

symbols of sexual emancipation in

France during the 1930s. Early in 1930,

she became popular as a singer, opening

a chic nightclub called Boîte de Nuit

which was one of the trendiest night

spots in Paris. Suzy Solidor did not hide

her sexuality and sang songs that overtly

revealed that she was gay. One of the

singer’s most famous publicity

achievements was to become heralded as

‘the most painted woman in the world’.

She posed for some of the best-known

artists of the day including Jean Cocteau

, Pablo Picasso , and Georges Braque.

Her stipulation for sitting was that she

would be given the paintings to hang in

her club. There are, in total, around 150

paintings of Solidor. In Cagnes-sur-Mer,

in the south of France, there is a museum

dedicated to her with a collection of 42

portraits all painted by different artists.

She died in 1983. It is not known

whether she sat for Gross or whether he

based his work on occasional sightings of

her at cabaret performances or on the

many paintings of her that would have

been accessible in Paris at that time.

The Silver Head

The silver head created by Gross is of

particular interest. One quality that this

work possesses is playfulness – it is

challenging, teasing, and puzzling. This

playfulness offers both illusions and

allusions. One moment the head seems

to be one thing, the next moment it is

something else. An extraordinary

feature of the head is that from the

reverse side, the head takes on the

appearance of a Cubist painting. The

muted palette of bronze, pink, steel blue

and grey are strongly reminiscent of

certain portraits by Picasso. There can be

few examples of sculpture that

mysteriously dissolves into what appears

to be a painting.

The colours are a natural result of the

process of oxidisation. We know that

some contemporary silversmiths

deliberately seek to achieve the oxidised

effect on their jewelry.

After her husband’s death Trude Sand

insisted that the head should be kept

highly polished and one must assume

that this stricture applied solely to the

exterior. What are the aesthetic

consequences? Whilst the polished

surface quite literally reflects the external

world, the oxidised interior invites the

viewer into it. The untreated side

provides an authentic face, whilst the

polished side provides an artificial face.

The head is teasing insofar as it presents

the viewer with a series of further

paradoxes. Whilst the exterior of an

object is usually that aspect that gains the

viewer’s attention, here it is the interior

that appears to possess more character

and meaning. What is particularly

intriguing is that Gross is inviting us to

see behind the mask, something that is

rarely done. It is as if a taboo has been

broken. To emphasise this feeling of

gaining new insights, we are presented

with a face in which the eye is dominant

and rather like the Eye of Horus – the

ancient Egyptian symbol of

indestructibility.

One of the most intriguing angles from

which to view the head is from the back.

Or is it the back? Gross would have been

aware of the work of Constantin

Brancusi, for he was working in Paris at

the same time as Gross. He would have

known of Brancusi’s minimalist

representations of the human face – The

Sleeping Muse. The strongly ovate

shape of the face of The Sleeping Muse

intentionally suggests an egg – a symbol

of birth or new life. In discussing the

nature of his work Brancusi coined the

striking aphorism that “simplicity is

complexity resolved”. So, when one

moves to a position to view the ‘rear’ of

the head, the intrinsic complexity of the

head magically resolves into a simple

Brancusian ovoid.

So, in this single artefact – the silver head

– we have allusions not only to different

artistic genres but also to symbols of

considerable power – indestructability,

birth, and rebirth. These, in turn, can be

interpreted as signs of resurrection and

hope – themes that Gross pursued

throughout his life. But then the

question may be asked: ‘How can one be

so confident that Gross was trying to

communicate any of these messages?

The simple answer is that we do not

know. But that question rather misses

the point. What Gross has succeeded in

doing is stimulating the viewer to reflect

on its meaning. The Silver Head is now

in the possession of Aberdeen Art

Gallery.

Gross left Paris in 1935 and returned to

Germany.