Scotland

In 1963, Gross decided to leave Germany and move to Scotland. Knowledge of

Gross’s work had been communicated through a network of friends to Dr Karl

Koenig, co-founder of the Camphill Movement. As a result of a meeting between

Koenig and Gross, an invitation was extended to Gross to come to Scotland. Gross

and Koenig not only shared a common language but also both recognized and

valued the spiritual dimension in art and ways of seeking to give artistic expression

to the human spirit.

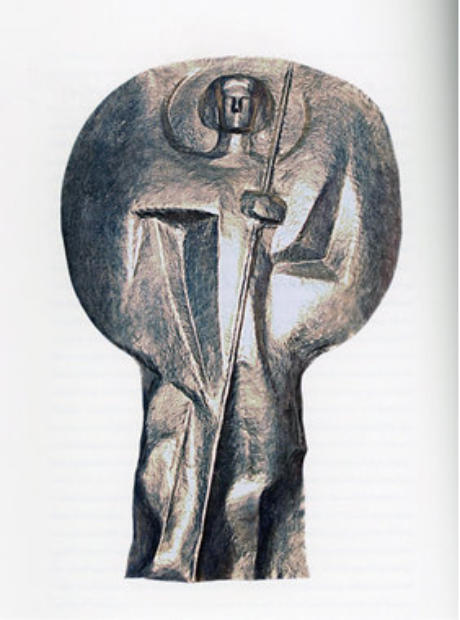

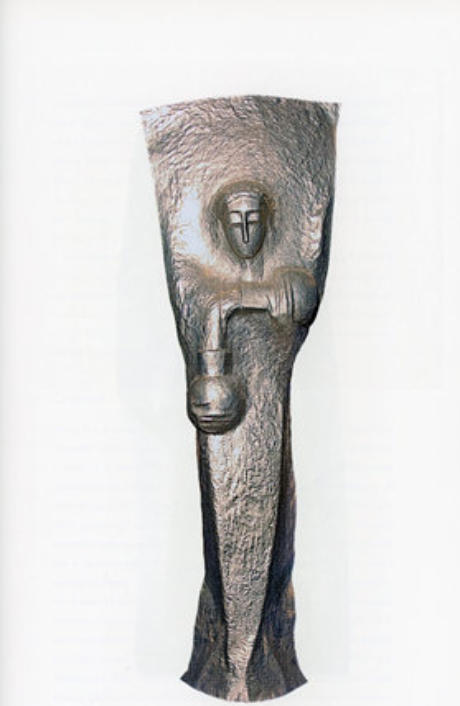

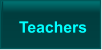

One of the reasons that Dr Koenig invited Gross to Aberdeen was to create a number

of sculptures for the newly constructed Camphill Hall that was to be the spiritual

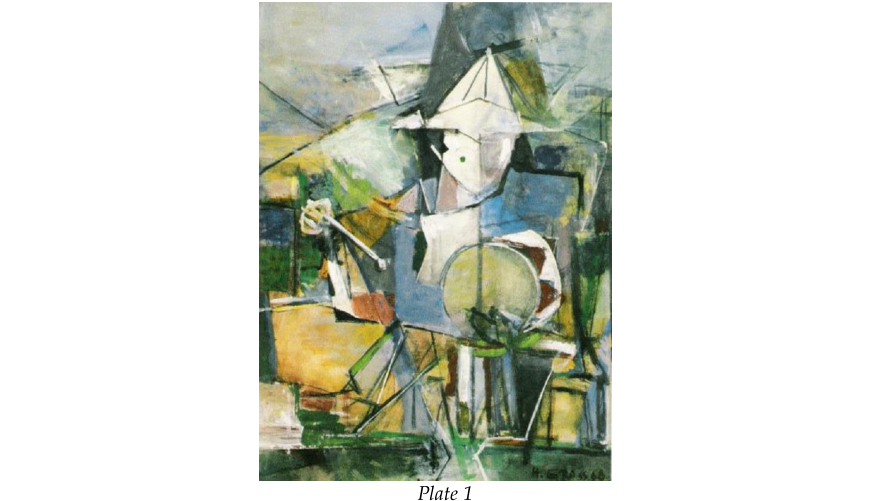

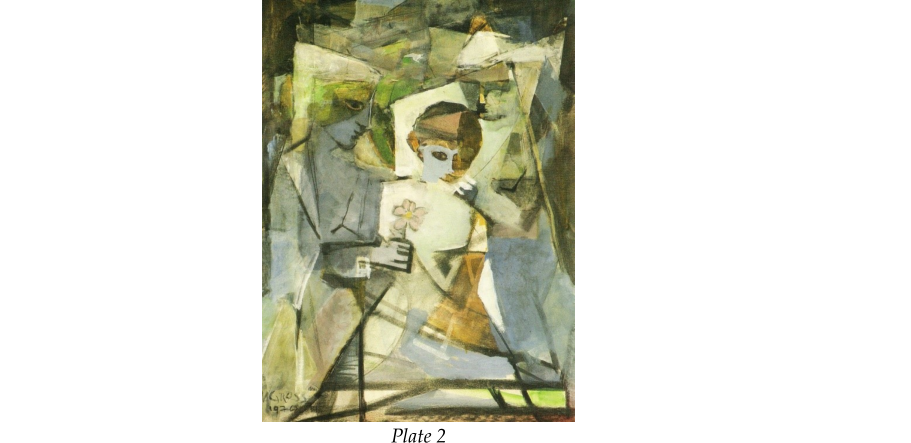

heart of the Camphill Movement. Plate One shows Michael the Archangel

representing peace and harmony, whilst Plate Two shows Raphael the Archangel

representing healing. The significance of these sculptures may reflect Dr Koenig’s

wish to develop at Camphill the discipline of curative education.

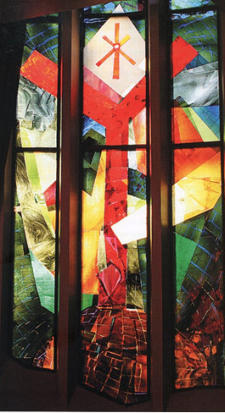

It is known that in the mid-1960s when he was considering the design of and method

of creating the stained-glass windows for Camphill Hall, he had visited Pluscarden

Abbey, a Benedictine Abbey in Morayshire. As virtually all the original stained glass

of the old abbey had been lost it was necessary to create new windows.

A new technique had been introduced which involved cutting and faceting thick

slabs of glass known as dalles de verre and setting them in a matrix of either epoxy

resin or concrete. An appealing feature of this method which was recognised by the

monks was the way in which the windows sparkled like jewels when in direct

sunlight.

The dominant feature in both stained glass windows is the Y figure. Throughout late

antiquity, the Y was an accepted pagan symbol of the choice between the hard path

of virtue (right) and the easy path of vice (left). The Y can also be seen as a tree

symbol related to the Christian cross and the Greek letter T (tau). Paintings in 15th

century Northern Europe often depicted the cross in Crucifixion scenes as a Tau cross

(e.g., Rogier van der Weyden, The Descent from the Cross, 1435). More significant

perhaps is the fact that Christ’s body would have assumed a Y shape given that his

wrists (not hands) were nailed to the horizontal cross beam. Whether or not there

was a mercy seat and/or platform upon which Christ’s feet rested, the weight of his

body would have led to a Y shape configuration. So, Gross may be alluding to

Christ’s agony on the cross.

Unlike many stained-glass windows or memorials, the abstract and three-

dimensional nature of the Camphill Hall windows brings them to life and makes a

strong, memorable, and vibrant visual impact.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Gross’s paintings had been explicitly religious

in content and were acknowledged by him to represent a working out of his own

inner emotional and spiritual turmoil. But with the passage of time and particularly

from the moment he assumed the role of artist-in-residence in Camphill the character

of his work underwent change.

Children as subjects in the art of Gross

As artist-in-residence at Camphill, Gross was able to show how art could provide a

powerful way of communicating profound insights about the nature of childhood to

those charged with the responsibility of caring for children and young people with

special needs.

Not only did Gross take children as his main subjects, but he went one step further

and encouraged the viewer to reflect upon the transient nature of childhood and all

the vulnerabilities inherent in it.

A distinctive feature of his work is that he did not give titles to any of his work as he

believed that attributing a title served as a distraction. His aim was for viewers to

arrive at their own interpretation and not be side-tracked by labels.

What is striking about Gross’s work is the way in which it seeks to address some of

the dilemmas faced by those caring for children. He was able to identify with many

often traumatised and bewildered children possibly because of his experiences

during the war when. He never fully recovered from this experience and something

of this continuing inner turmoil can be found in his paintings. Nevertheless in the

paintings he was able to communicate a strong, positive, and life-affirming message

to those working daily with the children in their care.

Gross was able to demonstrate how art can provide an effective medium for

conveying complex ideas about the nature of childhood and indicate possible ways of

nurturing and caring for vulnerable children. It is important to note that Gross never

gave titles to his paintings. He left it to viewers to place their own interpretation on

what they saw.

A significant feature of Camphill life is illustrated in Plate 1. In attempting to

communicate effectively with a child, the carer has to fall into step with the child, so

that they ‘dance to the same tune’. It is necessary, therefore, to listen to the ‘beat’ that

the child provides. The child and the carer then search for ways to establish and

maintain that joint rhythm, in a mutually inclusive way. It is necessary to learn to

listen, look, and explore in a new way, the pulse of groups with whom one works.

Rhythm is crucially important for it provides the impulse and framework that

enables often bewildered and disoriented children to experience for the first time a

measure of stability and security.

Rhythm is the living pulse that sustains the work of a healthy and healing

community. But the binding qualities of rhythm must not be confused with the

lockstep quality of the single drummer’s efforts to ensure conformity. True

rhythmicity, in contrast, requires a process of mutual engagement and inclusion, a

response to the beat of several drummers.

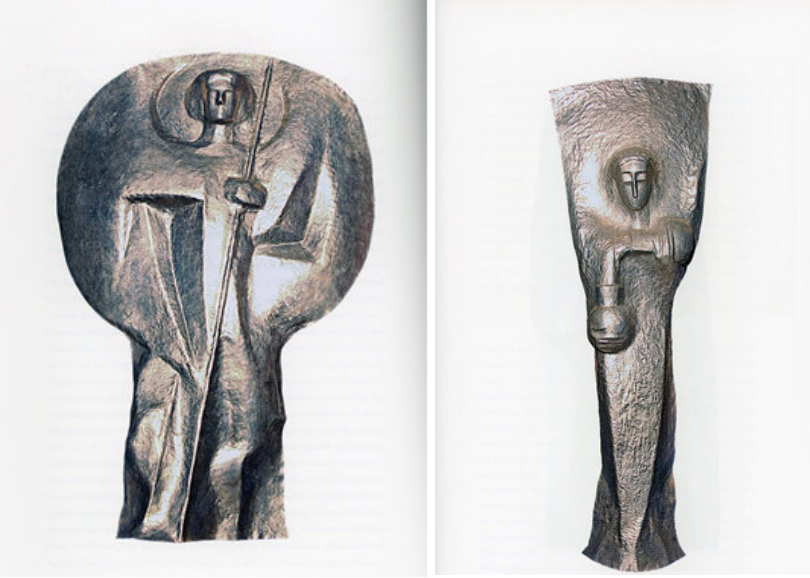

The dominant feature in Plate 2 is the eye of the child which looks out at and invites

the viewer into the painting. The subdued tones used in this palette convey an

impression of a tender and caring relationship between the child and the two adults –

possibly nurses – who stand on either side of him. There is no mawkish

sentimentality in this relationship. The painting successfully encapsulates the essence

of Camphill philosophy and practice, where the child is placed at the centre of its

work.

Gross’s experience of living in a community dedicated to the care of vulnerable

children and young people enabled him to communicate in a direct way the tender

and supportive character of the adult-child relationship.

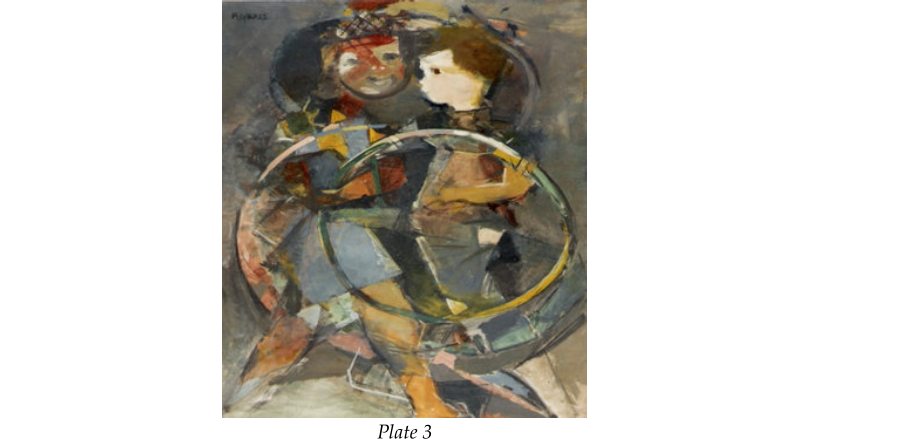

In Plate 3, which shows two children playing, Gross may be wishing to remind adult

viewers of the importance of play in a child’s life. It is not an incidental and trivial

activity but an important part of a child’s physical, social, and moral development for

play is the natural way for children to make sense of, and internalise, a whole range

of experiences. It offers the opportunity to explore ways of being, of establishing

identity and building self-esteem. The way the children’s bodies intersect

geometrically may be intended to convey the importance of social interaction. The

smile on the face of the child wearing the tartan bonnet is perhaps a reminder that

play is meant to be an enjoyable experience. The content of this painting has a strong

contemporary relevance. Play, whether formalised within the context of games or

recreational activities or stemming from the creative imagination of the individual

child, sadly has little place in the present-day mainstream curriculum. As a result, the

child experiences educational, cultural, and social impoverishment. But as Gross was

seeking to show an individual’s spiritual development is dependent upon

opportunities for free and creative self-expression.

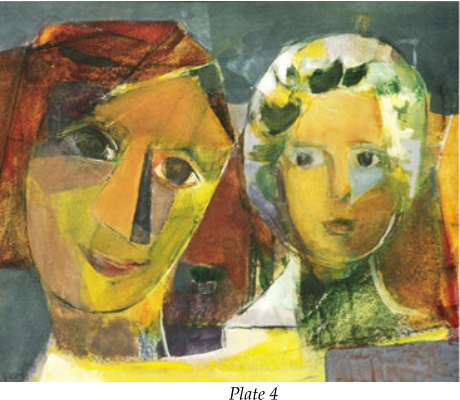

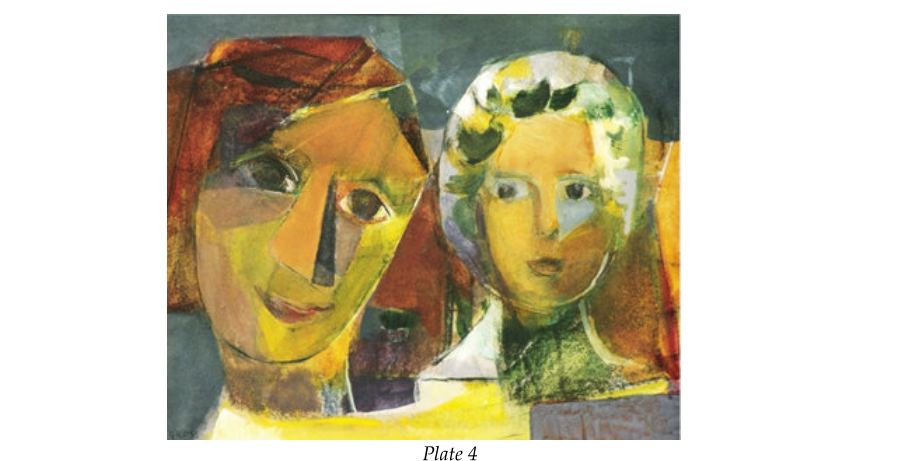

In Plate 4 we have the juxtaposition of the angular mask-like face of a woman with

the more realistically portrayed face of a child. What is Gross seeking to

communicate here? Is he suggesting that in the presence of children adults tend to

conceal their identity behind a mask? The child appears to be slightly behind the

woman and looking questioningly at her.

Children often find the behaviour of adults difficult to comprehend. Is Gross

intimating that the care offered by the adult has to be genuine and unconditional and

not feigned – not least because most children are sophisticated enough to make that

distinction? Whilst adults may attempt to hide behind a mask, children can

frequently see through it.

In the immediate aftermath of the war Gross’s paintings were explicitly religious in

content and were acknowledged by him to represent a working out of his own inner

emotional and spiritual turmoil. They were classic examples of German Expressionist

art. With the passage of time and particularly from the moment he assumed the role

of artist-in-residence in Camphill, the character of his work underwent a change.

The two themes of ‘masks and masquerades’ and ‘children in care’, which feature in

Gross’s work, pose questions about identity and mission: ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What is

my purpose?’ It is difficult to think of two more fundamental questions for anyone to

consider. However, long before the notion of ‘the reflective practitioner’ became part

of common professional parlance, Camphill co-workers were being constantly

encouraged to engage in professional reappraisal and spiritual reflection. Thus, they

were likely to be attuned to what Gross was seeking to communicate with them.

Whilst Gross may have had a target audience in mind, the content of his paintings

has a universal relevance and value. It needs to be remembered that these paintings

were not hanging in an art gallery but were located throughout the Community and

thus were constantly visually accessible.

The work of Hermann Gross is significant because it focuses on a neglected subject in

art – the child. He succeeds in different ways in capturing some of the quintessential

features of childhood which now appear to be under threat. For example,

opportunities for unsupervised play and recreation are limited by the growth of a

risk-averse culture which tends to extinguish spontaneity, creativity, and enjoyment.

At school, children are increasingly subject to a utilitarian approach to education

which emphasises the acquisition of certain basic skills and which attaches little

value to seeking ways of enhancing a child’s physical, social, and spiritual well-

being. Children also represent an extremely lucrative target for the omnipotent and

omnipresent marketing industry which, for commercial reasons, quite deliberately

exploits their susceptibilities. A report by the Children’s Society in 2006 indicated

that the state of childhood which had been the focus of Gross’s work was ‘under

threat’ or ‘disappearing’.

The significance of Gross’s work, which is sometimes subversive, often provocative

and always instructive, is that it illustrates the value of art as a way of

communicating profound insights about the nature of childhood to those charged

with the awesome responsibility of caring for children and young people. It also

provides us with a timely reminder of the precious nature of childhood and what we,

as a society, may be in danger of losing.

Gross’s work has remained generally unknown principally because he saw his

primary responsibility as that of acting as an artist-in-residence; producing art that

could be encountered in corridors, committee rooms and public halls throughout the

community.

A late discovery

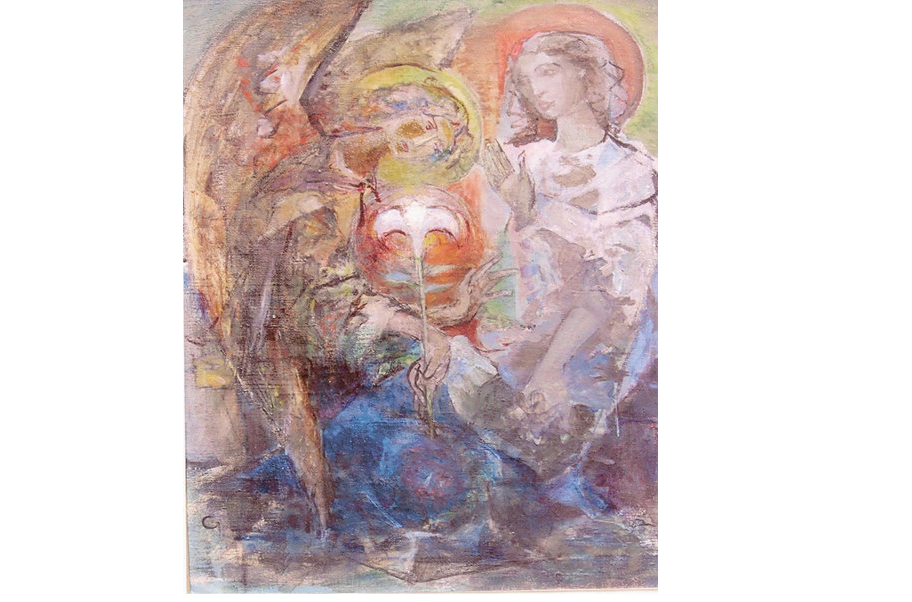

A short time after the biography of Hermann Gross was published in 2008 an email

was received from the USA conveying some intriguing news. A large number of

paintings had been discovered in the attic of a house in Vermont which had formerly

belonged to Hildegard Rath. What the owner of the house did not know was that

Hildegarde Rath had been the first wife of Hermann Gross. Someone acquainted

with the new owner of the house and who knew of Robin Jackson’s interest in the life

and work of both Hildegarde Rath and Hermann Gross, made contact. The

information was passed on that among many paintings found in the attic there were

two particularly large ones which were clearly not painted in the style of Rath.

Photographs of both paintings were sent to Scotland and were easily identified, not

simply because of their style and subject matter but because Gross’s monogram was

clearly visible at the bottom of each painting!

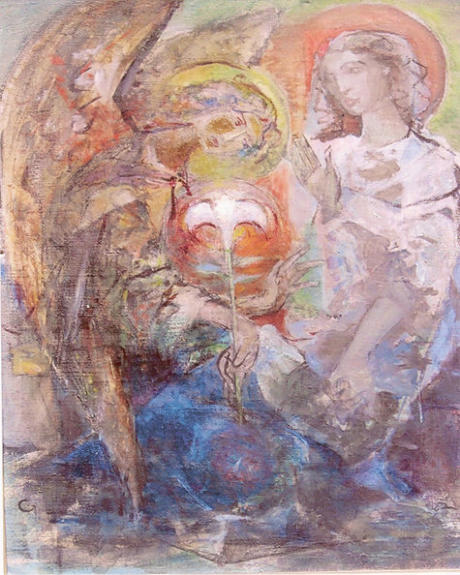

The painting illustrated here is of ‘The Annunciation’ where the Archangel Gabriel

announces to Virgin Mary the incarnation of Christ. This is one of the most frequent

subjects of artistic representation in both eastern and western Christian traditions. An

unusual feature in this painting is that both Mary and Gabriel are wearing halos, a

practice that was discontinued when artists sought to bring realism to their work.

What is interesting in Gross’s painting is that Mary is not wearing the royal blue robe

which features in most paintings of the Annunciation – Fra Angelico (1450),

Leonardo da Vinci (12472-5), Botticelli (1490), El Greco (1575). Here it lies on the

ground.

There can be little doubt that the focal point in this painting is the head of the lily

which seems to shimmer in a heat haze. Perhaps no other flower has more symbolic

associations than the lily. Indeed separate parts of the lily have been accorded

specific religious significance: the stem is said to symbolise Mary’s religious

faithfulness; the white petals stand for her purity and virginity; the stem represents

her divinity; and the leaves signify her humility.

At the same time, the lily – the funeral flower – symbolizes the departure of the soul

in death. Is the lily which is resting on the royal blue robe communicating another

message? Is the purplish glow where the lily stem touches the robe meant to indicate

that some powerful heavenly force is being transmitted through the lily stem to the

robe? And is there a faint likeness to a face in the robe itself where the end of the

stem touches the robe? In other words, is there a reference here to Christ’s bloodied

shroud? Is this purple stain a reminder of the purple robe that was offered by the

Roman centurion to Christ – the ‘King of the Jews’ – prior to his Crucifixion? And is

the fact that the robe itself resembles the shape of a mountain significant? Is this a

visual allusion to Mount Calvary where Christ was crucified?

Final thoughts

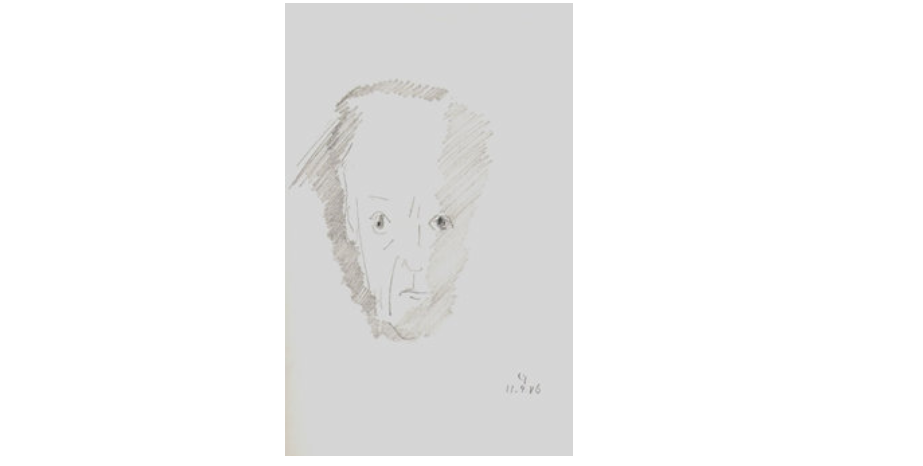

The time is long overdue for Gross’s talents as a sculptor, painter, and stained-glass

maker to be more widely recognised. Why is his work not more widely known? Part

of the answer lies in his decision to spend the latter part of his life working modestly

as an artist-in-residence in a small school in the North East of Scotland remote from

the artistic and intellectual heartlands of Paris, Berlin and New York. When Gross

came to Scotland, he abandoned a career in the ordinary sense of the word, for a

large part of a professional artist’s life is often devoted to seeking a market for his

work. Freed from concerns about remuneration, Gross no longer saw his works as

commodities for sale. It was in a Camphill community that he experienced one of his

most productive periods.

It is not unusual for a full appreciation of the unique qualities of an artist to be

delayed until some time after death. Such is the case with Hermann Gross. It is to be

hoped that what has been presented here demonstrates his supreme technical ability,

extraordinary versatility, and creative imagination. As Aline Louchheim, the doyenne

of New York art critics, observed in 1951, Gross was not only a true descendant of the

German Expressionist school but also someone who used that art form to

communicate a powerful spiritual message which was relevant to contemporary

society. His art continues to communicate that message.

Hermann Gross died on the 1st September 1988. A memorial tablet to Hermann

Gross and his wife, Trude, is located in the churchyard of Maryculter Parish Church,

Kincardineshire. The churchyard looks north over the River Dee and to the place

where Camphill was born in 1940.

Scotland

In 1963, Gross decided to leave Germany

and move to Scotland. Knowledge of

Gross’s work had been communicated

through a network of friends to Dr Karl

Koenig, co-founder of the Camphill

Movement. As a result of a meeting

between Koenig and Gross, an invitation

was extended to Gross to come to Scotland.

Gross and Koenig not only shared a

common language but also both

recognized and valued the spiritual

dimension in art and ways of seeking to

give artistic expression to the human spirit.

One of the reasons that Dr Koenig invited

Gross to Aberdeen was to create a number

of sculptures for the newly constructed

Camphill Hall that was to be the spiritual

heart of the Camphill Movement. Plate

One shows Michael the Archangel

representing peace and harmony, whilst

Plate Two shows Raphael the Archangel

representing healing. The significance of

these sculptures may reflect Dr Koenig’s

wish to develop at Camphill the discipline

of curative education.

It is known that in the mid-1960s when he

was considering the design of and method

of creating the stained-glass windows for

Camphill Hall, he had visited Pluscarden

Abbey, a Benedictine Abbey in

Morayshire. As virtually all the original

stained glass of the old abbey had been lost

it was necessary to create new windows.

A new technique had been introduced

which involved cutting and faceting thick

slabs of glass known as dalles de verre and

setting them in a matrix of either epoxy

resin or concrete. An appealing feature of

this method which was recognised by the

monks was the way in which the windows

sparkled like jewels when in direct

sunlight.

The dominant feature in both stained glass

windows is the Y figure. Throughout late

antiquity, the Y was an accepted pagan

symbol of the choice between the hard

path of virtue (right) and the easy path of

vice (left). The Y can also be seen as a tree

symbol related to the Christian cross and

the Greek letter T (tau). Paintings in 15th

century Northern Europe often depicted

the cross in Crucifixion scenes as a Tau

cross (e.g., Rogier van der Weyden, The

Descent from the Cross, 1435). More

significant perhaps is the fact that Christ’s

body would have assumed a Y shape given

that his wrists (not hands) were nailed to

the horizontal cross beam. Whether or not

there was a mercy seat and/or platform

upon which Christ’s feet rested, the weight

of his body would have led to a Y shape

configuration. So, Gross may be alluding

to Christ’s agony on the cross.

Unlike many stained-glass windows or

memorials, the abstract and three-

dimensional nature of the Camphill Hall

windows brings them to life and makes a

strong, memorable, and vibrant visual

impact.

In the immediate aftermath of the war,

Gross’s paintings had been explicitly

religious in content and were

acknowledged by him to represent a

working out of his own inner emotional

and spiritual turmoil. But with the passage

of time and particularly from the moment

he assumed the role of artist-in-residence

in Camphill the character of his work

underwent change.

Children as subjects

in the art of Gross

As artist-in-residence at Camphill, Gross

was able to show how art could provide a

powerful way of communicating profound

insights about the nature of childhood to

those charged with the responsibility of

caring for children and young people with

special needs.

Not only did Gross take children as his

main subjects, but he went one step further

and encouraged the viewer to reflect upon

the transient nature of childhood and all

the vulnerabilities inherent in it.

A distinctive feature of his work is that he

did not give titles to any of his work as he

believed that attributing a title served as a

distraction. His aim was for viewers to

arrive at their own interpretation and not

be side-tracked by labels.

What is striking about Gross’s work is the

way in which it seeks to address some of

the dilemmas faced by those caring for

children. He was able to identify with

many often traumatised and bewildered

children possibly because of his

experiences during the war when. He

never fully recovered from this experience

and something of this continuing inner

turmoil can be found in his paintings.

Nevertheless in the paintings he was able

to communicate a strong, positive, and life-

affirming message to those working daily

with the children in their care.

Gross was able to demonstrate how art can

provide an effective medium for conveying

complex ideas about the nature of

childhood and indicate possible ways of

nurturing and caring for vulnerable

children. It is important to note that Gross

never gave titles to his paintings. He left it

to viewers to place their own

interpretation on what they saw.

A significant feature of Camphill life is

illustrated in Plate 1. In attempting to

communicate effectively with a child, the

carer has to fall into step with the child, so

that they ‘dance to the same tune’. It is

necessary, therefore, to listen to the ‘beat’

that the child provides. The child and the

carer then search for ways to establish and

maintain that joint rhythm, in a mutually

inclusive way. It is necessary to learn to

listen, look, and explore in a new way, the

pulse of groups with whom one works.

Rhythm is crucially important for it

provides the impulse and framework that

enables often bewildered and disoriented

children to experience for the first time a

measure of stability and security.

Rhythm is the living pulse that sustains the

work of a healthy and healing community.

But the binding qualities of rhythm must

not be confused with the lockstep quality

of the single drummer’s efforts to ensure

conformity. True rhythmicity, in contrast,

requires a process of mutual engagement

and inclusion, a response to the beat of

several drummers.

The dominant feature in Plate 2 is the eye

of the child which looks out at and invites

the viewer into the painting. The subdued

tones used in this palette convey an

impression of a tender and caring

relationship between the child and the two

adults – possibly nurses – who stand on

either side of him. There is no mawkish

sentimentality in this relationship. The

painting successfully encapsulates the

essence of Camphill philosophy and

practice, where the child is placed at the

centre of its work.

Gross’s experience of living in a

community dedicated to the care of

vulnerable children and young people

enabled him to communicate in a direct

way the tender and supportive character of

the adult-child relationship.

In Plate 3, which shows two children

playing, Gross may be wishing to remind

adult viewers of the importance of play in

a child’s life. It is not an incidental and

trivial activity but an important part of a

child’s physical, social, and moral

development for play is the natural way

for children to make sense of, and

internalise, a whole range of experiences. It

offers the opportunity to explore ways of

being, of establishing identity and building

self-esteem. The way the children’s bodies

intersect geometrically may be intended to

convey the importance of social

interaction. The smile on the face of the

child wearing the tartan bonnet is perhaps

a reminder that play is meant to be an

enjoyable experience. The content of this

painting has a strong contemporary

relevance. Play, whether formalised within

the context of games or recreational

activities or stemming from the creative

imagination of the individual child, sadly

has little place in the present-day

mainstream curriculum. As a result, the

child experiences educational, cultural,

and social impoverishment. But as Gross

was seeking to show an individual’s

spiritual development is dependent upon

opportunities for free and creative self-

expression.

In Plate 4 we have the juxtaposition of the

angular mask-like face of a woman with

the more realistically portrayed face of a

child. What is Gross seeking to

communicate here? Is he suggesting that in

the presence of children adults tend to

conceal their identity behind a mask? The

child appears to be slightly behind the

woman and looking questioningly at her.

Children often find the behaviour of adults

difficult to comprehend. Is Gross

intimating that the care offered by the

adult has to be genuine and unconditional

and not feigned – not least because most

children are sophisticated enough to make

that distinction? Whilst adults may

attempt to hide behind a mask, children

can frequently see through it.

In the immediate aftermath of the war

Gross’s paintings were explicitly religious

in content and were acknowledged by him

to represent a working out of his own

inner emotional and spiritual turmoil.

They were classic examples of German

Expressionist art. With the passage of time

and particularly from the moment he

assumed the role of artist-in-residence in

Camphill, the character of his work

underwent a change.

The two themes of ‘masks and

masquerades’ and ‘children in care’, which

feature in Gross’s work, pose questions

about identity and mission: ‘Who am I?’

and ‘What is my purpose?’ It is difficult to

think of two more fundamental questions

for anyone to consider. However, long

before the notion of ‘the reflective

practitioner’ became part of common

professional parlance, Camphill co-

workers were being constantly encouraged

to engage in professional reappraisal and

spiritual reflection. Thus, they were likely

to be attuned to what Gross was seeking to

communicate with them. Whilst Gross

may have had a target audience in mind,

the content of his paintings has a universal

relevance and value. It needs to be

remembered that these paintings were not

hanging in an art gallery but were located

throughout the Community and thus were

constantly visually accessible.

The work of Hermann Gross is significant

because it focuses on a neglected subject in

art – the child. He succeeds in different

ways in capturing some of the

quintessential features of childhood which

now appear to be under threat. For

example, opportunities for unsupervised

play and recreation are limited by the

growth of a risk-averse culture which

tends to extinguish spontaneity, creativity,

and enjoyment. At school, children are

increasingly subject to a utilitarian

approach to education which emphasises

the acquisition of certain basic skills and

which attaches little value to seeking ways

of enhancing a child’s physical, social, and

spiritual well-being. Children also

represent an extremely lucrative target for

the omnipotent and omnipresent

marketing industry which, for commercial

reasons, quite deliberately exploits their

susceptibilities. A report by the Children’s

Society in 2006 indicated that the state of

childhood which had been the focus of

Gross’s work was ‘under threat’ or

‘disappearing’.

The significance of Gross’s work, which is

sometimes subversive, often provocative

and always instructive, is that it illustrates

the value of art as a way of communicating

profound insights about the nature of

childhood to those charged with the

awesome responsibility of caring for

children and young people. It also

provides us with a timely reminder of the

precious nature of childhood and what we,

as a society, may be in danger of losing.

Gross’s work has remained generally

unknown principally because he saw his

primary responsibility as that of acting as

an artist-in-residence; producing art that

could be encountered in corridors,

committee rooms and public halls

throughout the community.

A late discovery

A short time after the biography of

Hermann Gross was published in 2008 an

email was received from the USA

conveying some intriguing news. A large

number of paintings had been discovered

in the attic of a house in Vermont which

had formerly belonged to Hildegard Rath.

What the owner of the house did not know

was that Hildegarde Rath had been the

first wife of Hermann Gross. Someone

acquainted with the new owner of the

house and who knew of Robin Jackson’s

interest in the life and work of both

Hildegarde Rath and Hermann Gross,

made contact. The information was passed

on that among many paintings found in

the attic there were two particularly large

ones which were clearly not painted in the

style of Rath. Photographs of both

paintings were sent to Scotland and were

easily identified, not simply because of

their style and subject matter but because

Gross’s monogram was clearly visible at

the bottom of each painting!

The painting illustrated here is of ‘The

Annunciation’ where the Archangel

Gabriel announces to Virgin Mary the

incarnation of Christ. This is one of the

most frequent subjects of artistic

representation in both eastern and western

Christian traditions. An unusual feature in

this painting is that both Mary and Gabriel

are wearing halos, a practice that was

discontinued when artists sought to bring

realism to their work. What is interesting

in Gross’s painting is that Mary is not

wearing the royal blue robe which features

in most paintings of the Annunciation –

Fra Angelico (1450), Leonardo da Vinci

(12472-5), Botticelli (1490), El Greco (1575).

Here it lies on the ground.

There can be little doubt that the focal

point in this painting is the head of the lily

which seems to shimmer in a heat haze.

Perhaps no other flower has more

symbolic associations than the lily. Indeed

separate parts of the lily have been

accorded specific religious significance: the

stem is said to symbolise Mary’s religious

faithfulness; the white petals stand for her

purity and virginity; the stem represents

her divinity; and the leaves signify her

humility.

At the same time, the lily – the funeral

flower – symbolizes the departure of the

soul in death. Is the lily which is resting on

the royal blue robe communicating another

message? Is the purplish glow where the

lily stem touches the robe meant to

indicate that some powerful heavenly force

is being transmitted through the lily stem

to the robe? And is there a faint likeness to

a face in the robe itself where the end of

the stem touches the robe? In other words,

is there a reference here to Christ’s

bloodied shroud? Is this purple stain a

reminder of the purple robe that was

offered by the Roman centurion to Christ –

the ‘King of the Jews’ – prior to his

Crucifixion? And is the fact that the robe

itself resembles the shape of a mountain

significant? Is this a visual allusion to

Mount Calvary where Christ was

crucified?

Final thoughts

The time is long overdue for Gross’s

talents as a sculptor, painter, and stained-

glass maker to be more widely recognised.

Why is his work not more widely known?

Part of the answer lies in his decision to

spend the latter part of his life working

modestly as an artist-in-residence in a

small school in the North East of Scotland

remote from the artistic and intellectual

heartlands of Paris, Berlin and New York.

When Gross came to Scotland, he

abandoned a career in the ordinary sense

of the word, for a large part of a

professional artist’s life is often devoted to

seeking a market for his work. Freed from

concerns about remuneration, Gross no

longer saw his works as commodities for

sale. It was in a Camphill community that

he experienced one of his most productive

periods.

It is not unusual for a full appreciation of

the unique qualities of an artist to be

delayed until some time after death. Such

is the case with Hermann Gross. It is to be

hoped that what has been presented here

demonstrates his supreme technical ability,

extraordinary versatility, and creative

imagination. As Aline Louchheim, the

doyenne of New York art critics, observed

in 1951, Gross was not only a true

descendant of the German Expressionist

school but also someone who used that art

form to communicate a powerful spiritual

message which was relevant to

contemporary society. His art continues to

communicate that message.

Hermann Gross died on the 1st September

1988. A memorial tablet to Hermann Gross

and his wife, Trude, is located in the

churchyard of Maryculter Parish Church,

Kincardineshire. The churchyard looks

north over the River Dee and to the place

where Camphill was born in 1940.